By Matthew C. Caston,

Guest Writer, CEO & Founder, Freedman Society,

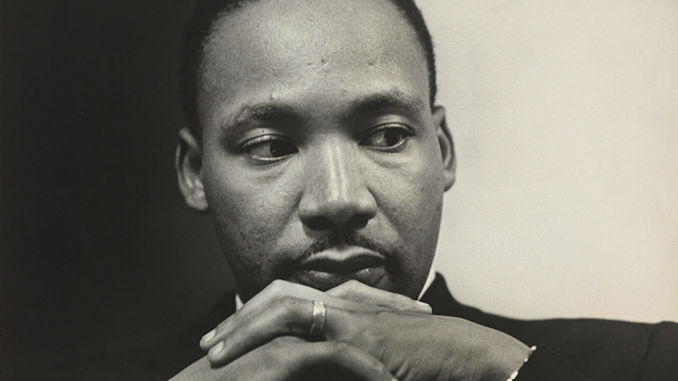

“Who is it that is supposed to articulate the longings and aspirations of the people more than the preacher?” Dr. Martin Luther King asked a crowd of almost 2,000 people April 3, 1968, at Bishop Charles Mason Temple in Memphis, Tenn. It was the height of the sanitation worker’s strike where 1,300 Black men had been protesting for fair wages, equal treatment and union recognition since the death of two fellow employees February 1.

Although exhausted from traveling and leading and organizing civil rights efforts across the Deep South, King was persuaded by the crowd to speak.

In his famous I’ve Been to the Mountaintop speech, King breathed new life into the movement in Memphis. “Somehow the preacher must have a kind of fire shut up in his bones,” he said. Fire he had.

Born January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Ga., King grew up in a nation that refused to recognize him as a citizen deserving of the same rights and privileges granted to his white counterparts. Attending segregated schools, living in the apartheid South and watching his father challenge the Jim Crow system directly influenced King from an early age.

Channeling his anger and focusing his fire would be a key part of King’s development into the legend he would become.

King’s legacy began with the love and teachings of his family. He attended Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta where his father pastored. He was active in worship, singing in the choir and memorizing bible verses and hymns by the time he was five.

As a child, King struggled to understand the society in which he found himself. According to Alice Fleming’s Martin Luther King Jr.: A Dream of Hope, King constantly contended with his anger and frustration with the racism and injustices of the Jim Crow South. According to Stephen Oates’ Let the Trumpet Sound: The Life of Martin Luther King, Jr., King attempted to take his own life twice: once after blaming himself for his sister’s injury and another in 1941 after the death of his grandmother.

An avid reader, King, played the violin and piano as a child. He became known for his ability to speak and joined the debate team at Booker T. Washington High School. In 1944 he gave his first public speech as a high school junior: The Negro and the Constitution. At 15, King simultaneously voiced his disappointment and desire in seeing a nation that had yet to live up to its democratic values.

His speech won first place in an oratorical contest sponsored by the Black Elks and can be found online at The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

That same year Dr. King enrolled at Morehouse College, where his father and maternal grandfather also attended. At Morehouse, King obtained a Bachelor of Arts in Sociology. He later obtained a Bachelor of Divinity from Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania where he was one of only six black students and was elected class president. He obtained a Doctor of Philosophy in systemic theology from Boston University.

While a champion of nonviolent direct action, King was also a master of delivering sober analyses and realism in his speeches and letters. From a childhood of fighting to understand a nation that saw him as less than human, to studying and working alongside some of the most impactful theologians and scholars in the nation, King had learned to temper and focus his fire.

“We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights,” King wrote in 1963 in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail. “The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jet-like speed toward the goal of political independence, and we still creep at horse and buggy pace toward the gaining of a cup of coffee at a lunch counter.”

His direct appeal to the white clergymen who voiced caution of peaceful protest in Birmingham shook not only state and federal leaders, policymakers and local clergy, but the soul of the nation.

“History is the long and tragic story of the fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily,” King wrote in the letter. “Individuals may see the moral light and give up their unjust posture; but as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups are more immoral than individuals.”

King reminds us of the power of community. In the same letter, he also reminds us of the collective and individual obligation we have in affecting change. “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

Toward the close of his letter, King makes a direct appeal to the conscience of America, to the fidelity of its constitution and validity of its beliefs.

“There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into an abyss of injustice where they experience the bleakness of corroding despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.”

King’s speeches and letters leave a legacy of activism, justice and standing strong in the face of adversity.

Alissa Funderburk, Oral Historian at the Margaret Walker Center at Jackson State University, stressed the importance of storytelling and oral tradition in the Black community in creating intergenerational change.

“Black people in America, being formerly enslaved, weren’t given the opportunity to learn to read and write. In those times, storytelling was critical and verbal accounts are the only things available to share their history.”

“Even as education became more and more important to Black people, storytelling still remained an important part of our community,” she said.

Funderburk, who has worked at the Margaret Walker Center since 2020, also emphasized the power of storytelling in preserving Black culture. “Passing down traditions and recipes, communicating and community building: all these things led to the rich culture and identity we have today. Storytelling remains the way in which we operate as a society. Especially nowadays as the news and internet is so easily tainted by misinformation. We have to trust our personal experience and the experience of the people we know.”

When asked what responsibility we have in continuing the tradition of storytelling and following Dr. King’s example, Funderburk was very clear.

“It’s every person’s responsibility to preserve their own legacy and the legacy of their ancestors. We have to build knowledge together. It’s poignant to think about what Dr. King wanted black people to do: speak up, advocate for yourself, and share your experience. We don’t do anything alone; we don’t achieve very much alone. And Dr. King and his legacy are important emblems of the power of coming together.”

King left a legacy of radical social change, powerful peaceful protests and speeches and writings that changed the course of this nation. His leadership, work and words have inspired generations of Americans to work toward a more perfect union. His life has inspired people across the world to petition for equality, equity and true democracy. His legacy is a testament to the tenacity and nobility of Black people in ensuring the rights and privileges of all citizens of this nation.

King leaves an example of how all people can channel their fire into direct action.

The Margaret Walker Center will be holding its annual convocation at Jackson State University Friday, Jan. 16 at 10 a.m. For more details go to https://www.jsums.edu/margaretwalkercenter/events/.

MLK Celebration Weekend hosted by Two Mississippi Museums from 1/16 to 1/20. Go to https://www.mdah.ms.gov/mlk2026 for a full calendar of events.

Be the first to comment