By Daja E. Henry,

In partnership with The Marshall Project,

Charles Caldwell was never meant to have a voice. Mississippi’s White ruling class made sure of it.

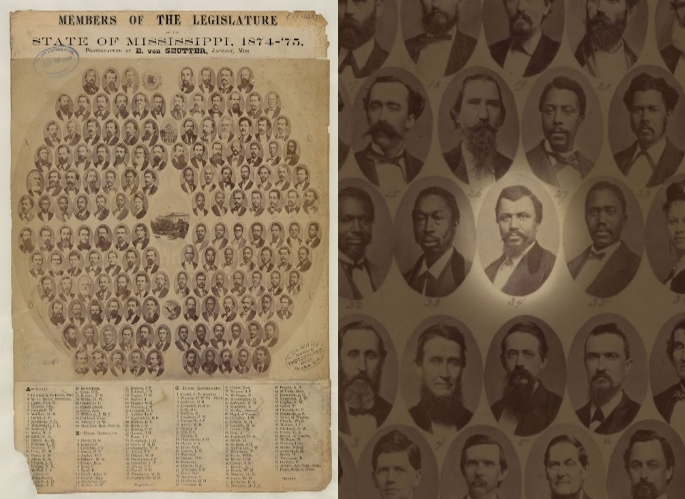

He was part of Mississippi’s silenced majority in 1860 – over 436,000 enslaved people to 354,000 White people – who would be granted full citizenship after the Civil War.

By 1868, Caldwell was one of 16 Black delegates at the state’s constitutional convention. By December 1875, he was assassinated.

His murder was part of the Mississippi Plan, an effort by outnumbered White men to maintain political control. White supremacists used lynchings, massacres and intimidation to silence the formerly enslaved, then cemented racism into the state’s 1890 constitution to further restrict the Black vote.

Part of the plan haunts Black voters today. Felony disenfranchisement, in Section 241 of the state’s constitution, permanently strips the right to vote upon conviction for several low-level crimes that the drafters of the 1890 constitution felt would be mostly committed by Black people. The clause has since been expanded and interpreted to cover 102 crimes.

Over the past 30 years, approximately 55,000 Mississippians have lost their rights to vote due to felony disenfranchisement. About six out of 10 are Black, according to state conviction records reviewed by The Marshall Project – Jackson.

Why was voter disenfranchisement created? In 1890, state Rep. James K. Vardaman, who would later be elected governor, said, “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter. … Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the [n-word] from politics.”

Yet as the civil rights organizing in the 20th century stripped away most voting restrictions, felony disenfranchisement remained. A bill to restore voting rights to some nonviolent offenders died in the state Senate on April 2, 2024.

“Movements change, but commitments don’t,” said Flonzie Brown Wright, the first Black woman in the state elected to public office in a racially mixed town. “Call it whatever you want to call it,” Brown Wright told The Marshall Project – Jackson. “But the common denominator is: Let’s [not] give these minorities any power.”

Civil rights gains – and new ways to stop them

Mississippi is one of 13 states that imposes a lifetime voting ban. In most of those states, lifetime disenfranchisement is for violent crimes or government corruption. In Mississippi, a single felony conviction for writing a bad check takes away the right to vote. Across the nation, courts and state legislatures have restored voting rights for people convicted of felonies. Mississippians last amended Section 241 in 1968 – to add murder and rape as disenfranchising crimes.

The Mississippi Plan effectively suppressed the Black vote in the 19th and 20th centuries, and its offshoots continue to evolve, historians say. Between 1875 and 1892, the number of Black voters plummeted. About 67% of eligible Black men had been registered in 1867. Fewer than 6% were registered by 1892, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Starting early in the 20th century, Black Mississippians left the state in droves. By 1940, Black people were no longer a majority. The Black vote in Mississippi remained largely dormant until the 1960s. Black people who remained in Mississippi faced much of the same oppression as their ancestors: lynchings, beatings, intimidation and imprisonment. After a 1963 voter registration workshop, civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer was arrested, sexually assaulted and beaten so brutally that it left her with kidney damage and a permanent limp.

The federal Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, protecting the right of Black citizens to vote. By 1968, 60% of eligible Black Mississippi residents had registered to vote, and Mississippians elected their first Black state legislator since Reconstruction, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Carroll Rhodes, a civil rights attorney, said that following the Voting Rights Act, local officials devised devious ways to make it difficult for Black people to register and vote.

Brown Wright won her race for the elections commission in Canton, MS in 1968, despite a rule change that required her to win votes across all parts of Madison County, instead of just the single district she would represent. After she took office, she said the board routinely denied her poll worker nominees who had been community activists and disqualified Black candidates. She sued to overturn the discriminatory actions and won. White people “never intended for Blacks to supersede or give the perception that we were in the process of gaining some semblance of equality. It was never intended to be,” Brown Wright, now 81, told The Marshall Project – Jackson.

Mass incarceration as modern voter suppression

At the same time that Mississippi’s civil rights activism gripped the nation, a conservative movement laid the foundation for tough-on-crime rhetoric that eventually took hold among both major political parties and fueled the escalation of arrests and mass incarceration. The key to the new rhetoric was erasing any mention of race. Instead, this new movement championed by both political parties used crime as coded language to exploit white supremacists’ fears and target Black people, attorney and civil rights scholar Michelle Alexander wrote in “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.”

Tough-on-crime rhetoric fueled initiatives like the war on drugs and harsh sentencing. Mississippi now incarcerates more people per capita than any other state. About 60% of incarcerated people in the state were Black in 2022. Though not all incarcerated people have lost their right to vote, a lack of information about who can and can’t vote makes it difficult for many affected by the legal system to access ballots.

However, lawmakers in both parties have tried to change the law. In 2008, and again in March 2024, the Mississippi House passed bills to restore voting rights to the disenfranchised for some nonviolent offenses, but both failed in the state Senate. In 2023, a U.S. Circuit Court panel ruled the lifetime voting ban unconstitutional, but an appeal is pending, leaving the law unchanged.

“There will always be a constant struggle. I learned that early on,” said Rhodes, the civil rights attorney. “The forces that want to undo the progress that’s been made will always be there.”

Visit The Marshall Project – Jackson at https://www.themarshallproject.org/jackson/ for more stories about the Mississippi justice system.

Published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system.

Be the first to comment