By Gail H. Marshall Brown, Ph.D.,

Contributing Writer,

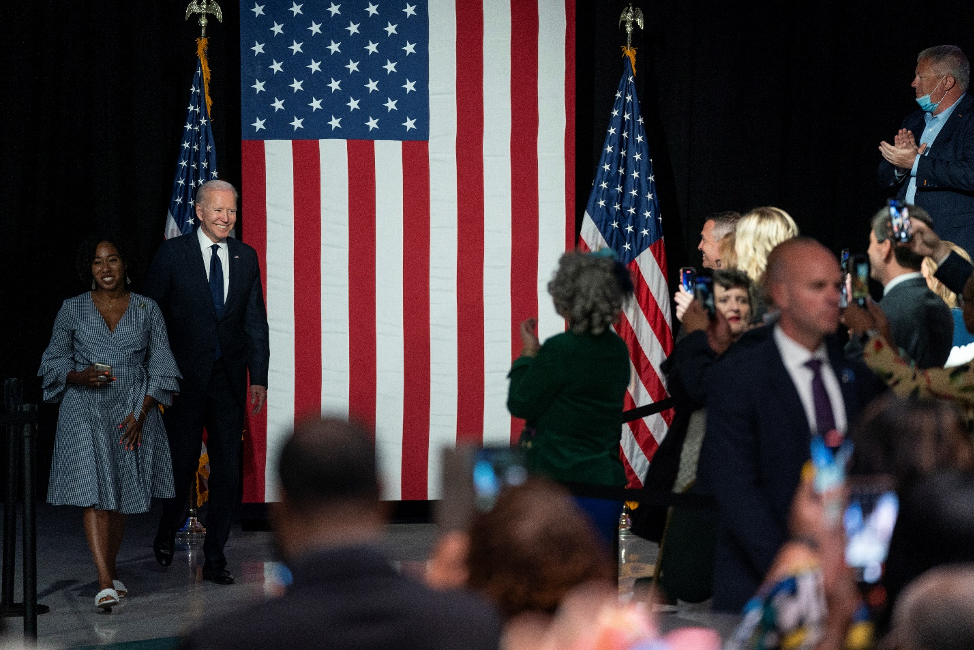

When President Joe Biden emphatically stated, from Tulsa, Okla., “My fellow Americans, this was not a riot; this was a massacre,” his audience burst into applause June, 1.

The 46th President of the United States was in Tulsa to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

The May 31, 1921 massacre took place as a white mob violently attacked black residents, destroyed and burned their homes and businesses in the-then prosperous black Greenwood District and business hub known as “Black Wall Street.” After 16 hours of violence, the horrific event left as many as 300 dead, 35 city blocks destroyed and thousands of blacks displaced.

Biden is the first sitting president to visit and commemorate the event which is a piece of history that many Americans are just learning about through recently televised documentaries and media reports on and leading up to its centennial.

“I was sick to my stomach,” expressed Betty McRee of Jackson, Miss. after she watched Monday night’s (May 31) CBS documentary, “Tulsa 1921: An American Tragedy.” “I cried and thought about Emmitt Till [because] the hold thing started because of a white woman’s allegation. But jealousy was the main motive,” McRee said.

Leslie Greer, a native of Lexington, Miss. and board president of a local non-profit, the Community Students Learning Center, was also amazed as he watched the Tulsa documentaries. “I had never heard about it,” Greer said.

Although highly disturbed by the massacre, he was impressed to know that blacks back then had the drive to create wealth in their community. “That’s something that I have always tried to stress among family and others,” he said. Greer is also founder and operator of Capitalist Wealth Makers, Inc.

Antwan Clark, an IT specialist, also of Lexington, had no prior knowledge of the massacre. “It was really heartbreaking to see how many black lives were lost, and the pain and heartache the survivors went through,” Clark said. “It was hard to watch and see what happened to so many of our black people and how their promising businesses were completed destroyed.”

Memphis native Elder Gregory Crenshaw, a retired public school educator, described the century-old event as “another heinous hate crime committed against people of color in America and nothing done about it.”

Not only did McRee, Greer, Clark and other Americans not know about this tragic event, there were people growing up in Tulsa who had not heard about it, according to the documentaries.

Crenshaw said he had heard about the incident prior but “white America pushed it under the rug.”

“Literal hell unleased,” described President Biden, who also met with survivors during his Tulsa visit.

For years, the Tulsa Race Massacre was kept out of the history books. Even during its happening and after, it is alleged that the media was asked to squashed the story.

North Tulsa native Dewayne Dickens, Ph.D., told The Mississippi Link in a telephone interview that people in Tulsa simply did not talk about it, “in the black community nor white community.” He said he thinks the blacks did not want to talk about it out of fear and the whites (many of them) were ashamed.

Dickens, who serves as director diversity, equity and inclusion at Tulsa Community College, said that there is still some “mixed perspective” on discussing it today.

An example of media squashing the story was Ed Wheeler’s 1970 writing project, “Profiles of a Race Riot.”

Wheeler, a Tulsan native who is white and a captain in the National Guard infantry battalion at the time, met strong opposition including treats. It was refused by the first publisher, but he was persistent and eventually got it published.

With this week’s recent 100-year observance, no doubt media around the nation and the world are reporting on the event. What was once Tulsa’s dirty little secret is being told.

Children in Tulsa Public Schools will have the opportunity now to learn about it. Thanks to the Burt B. Holmes and George Kaiser Family Foundations, the Tulsa World to TPS “to assist in teaching about the Tulsa Race Massacre in the classrooms,” the paper’s introduction indicated.

“As a black journalist, I am fortunate to have had the opportunity to be one of the contributors to our archival publication which will educate young people about this horrible event for years to come,” said Kendrick Marshall, assistant city editor at the Tulsa World. Marshall, a Chicago native and current Tulsa resident, is a 2006 Jackson State University Mass Communications alumni who freelanced for the Black Press papers in Jackson while living there.

Some Tulsans are pleased that some light is finally being shed on their city’s dark history.

Kavin Ross, photojournalist, owner and publisher of weekly Greenwood Tribune, was “honored” to be contacted by The Mississippi Link newspaper.

“My great grandfather Isaac Evitt’s Zulu Lounge was destroyed in the Tulsa Massacre,” Ross said. “The freeway now runs over top where it used be,” he said.

Ironically, the section of Interstate 244 that towers over where Ross’ great grandfather’s lounge was located is named for the nation’s iconic drum major for non-violence and peace: “The Dr. Martin Luther King Memorial Expressway.”

Speaking of interstate, many now are posing the question: The secret is out; generational wealth went up in flames; many lives lost and impacted; no one held accountable: where do we, not just Tulsa, go from here?

“I feel the families should be given reparation for the properties they lost and money for insurance payments they were denied,” stressed McRee.

Dickens, who serves on the Board of Directors for Tulsa’s John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, where he chairs the Annual Symposium, said he would like to see restorative justice. “At the end of the day, there has to be a sense of hope,” he said.

Dickens also said education, conversation and urban planning for the area are keys to repairing that district to its original state; creating another Black Wallstreet.

“If those people did it 100 years ago, we could have economically prosperous communities of color today,” concluded Crenshaw, on location in Mississippi.

Be the first to comment