MUMBAI, India — Every year, 28-year-old Durgesh Mandal — a domestic worker and helper in an apartment in India’s financial capital Mumbai — goes back to his village, Havi Bhouhar in the Darbhanga district of the eastern state of Bihar, for a month to spend time with his wife and three kids.

Durgesh is among the scores of daily wagers who work as agricultural laborers in the rural areas during the sowing season and as house helps or on construction sites in the urban areas during the off-season. His earnings are meager at $6 for a day extending up to 18 hours.

On March 24, 2020, just a week before he was about to return to Mumbai from his village, the Indian government announced the nationwide lockdown to control the country’s spread of the Covid-19 virus.

“Normally, I’m unable to save much from my monthly salary. After the lockdown was announced, we ran out of money in a few weeks because I couldn’t return to work,” said Mandal, who received no salary or help from his employers during the lockdown.

The number of people in India’s middle-income group, which comprises people earning between $10.01 and $20 daily, has shrunk by 32 million in 2020 because of the Covid-19 recession, according to an analysis by Pew Research Center released in March.

The number of poor people — earning a maximum of up to $2 a day — rose by 75 million owing to Covid-19 induced recession. The figures represent a staggering 60 percent of the global increase in poverty, the study notes.

Over 122 million people lost their jobs due to the lockdown distress, with daily wagers, laborers, and small traders accounting for over 91 million of the jobs lost within April 2020. In May 2020, India’s unemployment rate, already at a six-decade high, rose to 27.1 percent.

“I had no choice but to borrow INR 25,000 ($335) from someone in the village as I had to put food on the table for my family,” said Mandal, who could be considered fortunate despite his dire circumstances, given what unfolded for other migrant workers when the lockdown commenced in March 2020.

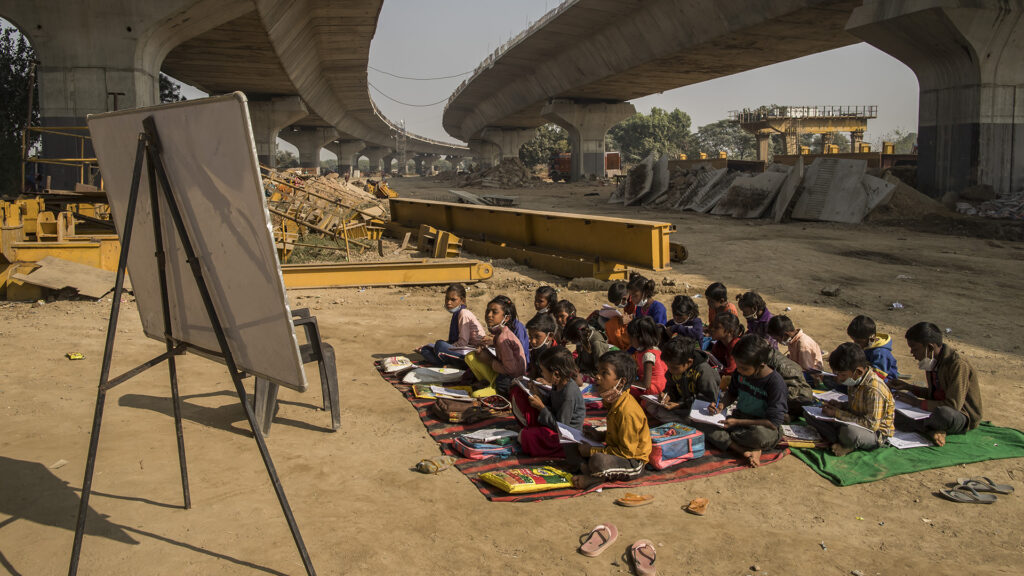

With no food, shelter, and jobs, migrant workers and their families were stranded in cities. The lack of availability of public transport due to the lockdown left many with no option but to journey — lasting days to weeks — back to their villages, many on foot.

This resulted in 971 deaths (unrelated to Covid-19), including 96 workers who died on trains (organized from May 1, 2020, onwards to ferry the migrant workers home). Over 11.4 million migrants returned to their homes.

“With no formal registration and enumeration of migrant workers, the true estimates of the number of migrant workers, including those who returned to their villages during the lockdown, are much larger,” Divya Varma, program manager, Centre of Migration and Labour Solutions at Aajeevika Bureau, told Zenger News.

“When migrant workers stop remitting money back home, it has a cascading effect on the rural economy as well,” Benoy Peter, executive director at the Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development in Kerala, told Zenger News.

Between 2005 and 2016, around 273 million people in India were lifted out of multidimensional poverty, according to a study by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative and the United Nations Development Programme released in 2020.

Among the welfare schemes undertaken to facilitate this, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Generation Guarantee Act (MNREGA), 2005, mandated the provision of at least 100 days of guaranteed wage employment in a financial year to every rural household whose adult members volunteered to do unskilled manual work.

The stark rise in unemployment caused due to the lockdown is also reflected in the higher number of jobs demanded through the MNREGA.

Over 133 million people demanded work through the rural jobs program in 2020-21, of which over 111 million got work. A 43 percent rise compared to the 93 million who demanded work and 78 million who were offered work through the program in 2019-20.

“The MNREGA has had many complications in its implementation. Many people still choose to migrate due to poverty. The collection of data is crucial to tackling this problem,” said Peter.

There is no credible data on India’s migrant workers yet. The government is developing a National Database of the Unorganized Workers, as per an answer put forth during a parliamentary session on March 22, 2021.

To tackle the rising poverty, the government doled out relief measures such as providing 800 million beneficiaries with a monthly ration of 5 kilograms (11 pounds) of wheat or rice and 1 kilogram of preferred pulses, free of cost till November 2020.

Many experts pegged the quantities as “very less” to feed a family of at least three for a month.

The government also launched the ‘Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyaan’ to provide employment to the rural population (including returnee migrant workers) in six states and create an infrastructure through 25 target-driven works with funding of around INR 500 billion ($6.7 billion), of which it utilized INR 392 billion ($5.3 billion).

“This would help not only the returning migrants but the rural population as a whole. The implementation at the grassroots level is key,” Peter said.

The construction sector contributes to around 9 percent of India’s Gross Domestic Product and employs 55 million daily-wage workers. The government also disbursed around $670 million to 18.3 million building and other construction workers, but “there were issues regarding cash transfers to the workers”.

But these relief measures did not provide a long-term solution to the distressed rural economy. Around five months after the migrant workers left the cities, many, including Mandal, returned due to the lack of opportunities in villages, as per a rapid assessment survey.

The case was similar this year, if not worse when the second wave of the Covid-19 virus gripped India. A lockdown in Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh and cities such as the national capital Delhi once again forced migrant workers to go back to their villages. The images were albeit less haunting compared to last year.

“Last year, we had to go back home due to the lockdown, which caused a lot of financial problems because my mother had to undergo surgeries within the past year,” Sahil, an 18-year-old who works at a shopping mall in Goregaon Mumbai, told Zenger News. He was at the Lokmanya Tilak Terminus in Kurla, Mumbai, holding a train ticket.

Sahil and his father — a daily-wage-earning carpenter — were lucky enough to get a ticket to their home in Azamgarh, a city in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, amid a sudden surge in migrants wanting to go home.

“We borrowed over INR 150,000 ($2,000) for the surgeries. We came back to work in Mumbai this March [2021], and in less than a month, we have to leave again. It’s harder this time around because my father, who is with me now, has a problem in his liver [according to a doctor], and I don’t know what will happen next.”

Many migrant workers and their families were spotted waiting outside a partition made in the exteriors of the railway terminal to purchase an outstation train ticket.

On April 20, India’s Ministry of Labour and Employment restarted 20 control rooms dedicated to addressing the grievances of migrant workers “through coordination with various state governments”.

“In some scenarios, migrant workers are returning home in very crowded and packed general compartments. This could have serious implications, and we cannot rule out a rural epidemic. It’s coming down to how resilient one can be to cope in distress,” said Peter.

Since then, daily cases in India have consistently crossed the 300,000-mark for the past week.

(Edited by Gaurab Dasgupta and Abinaya Vijayaraghavan.)

The post Covid Crisis Pushed 75 Million Indians Into Poverty In 2020, Study Claims appeared first on Zenger News.