Scientists may have discovered a new way to treat obesity — a health problem affecting more than 40 percent of American adults — by using fat and skinny genes.

Experts at the University of Virginia have identified 14 genes that cause weight gain and three that help prevent it.

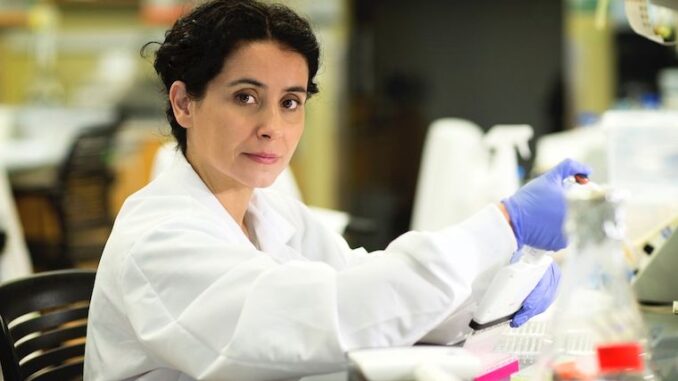

“We know of hundreds of gene variants that are more likely to show up in individuals suffering obesity and other diseases. But ‘more likely to show up’ does not mean causing the disease,” said Eyleen O’Rourke of the University of Virginia. To address the uncertainty, O’Rourke said the research team developed a method to “test hundreds of genes for a causal role in obesity.”

During the first round of experiments, the team made a discovery that, according to O’Rourke, “will accelerate the development of treatments to reduce the burden of obesity.”

The study, published in the journal PLOS Genetics, noted that sedentary lifestyles and high-calorie diets laden with sugar and high-fructose corn syrup contribute to obesity, but genes play a role in metabolism and fat storage. By identifying the genes that convert food into fat, scientists can develop drugs to deactivate them, uncoupling excessive eating from obesity.

While hundreds of genes are associated with obesity, experts sought to find which of them directly promote or prevent weight gain. The study used a worm-like nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, which is about 1 mm long and feasts on microbes living in rotting vegetation. C. elegans is used as a model organism, for instance, to understand how the antidepressant Prozac and the glucose-stabilizing metformin work. Because they share 70 percent of our genes, these nematodes also fatten when given too much sugar.

For the study, the team used the nematodes to screen 293 genes associated with obesity, feeding some a regular diet and some a high-fructose diet. They found 14 genes that cause obesity and three that block it and lead to longer lives.

Using lab mice, researchers blocked one of the genes that encouraged obesity and found it prevented weight gain, lowered blood sugar and improved uptake of insulin, all of which are also associated with diabetes. The team is confident that similar results will be seen in human subjects.

“Anti-obesity therapies are urgently needed to reduce the burden of obesity [on] patients and the healthcare system,” O’Rourke said. “Our combination of human genomics with causality tests in model animals promises yielding anti-obesity targets [that are] more likely to succeed in clinical trials because of their anticipated increased efficacy and reduced side effects.”

Edited by Siân Speakman and Kristen Butler

The post Scientists Block ‘Fat Gene’ In Lab Mice, Preventing Weight Gain And Lowering Blood Sugar appeared first on Zenger News.