By Julio Guzmán

MEXICO CITY — Ten women died every day in Mexico from violence in the first half of 2020 — one of the most violent periods in the country in the last 30 years. That totals 1,844 women, according to Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics.

Femicides — the violent death of women for gender reasons — make up a large part of these figures.

From January to May 2021, victims’ relatives reported 412 femicides in the country, 7 percent more than the previous year. Mexico City, one of the most populated areas in the country, ranked fourth on the list, with 35 cases, while the State of Mexico ranked first, with 77.

But not everyone reports femicides — and the actual figures could be even higher.

Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who claimed in previous months that 90 percent of the emergency calls reporting violence against women were false, publicly acknowledged the problem. “Unfortunately, there has been an increase in femicides, in family violence; we are working on that,” he said in June at a press conference.

A second issue is prosecution language.

The organization Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad estimates that 46 of every 100 murders of women should be classified as femicides. Instead, they are labeled as intentional homicides, increasing the chances of going unpunished.

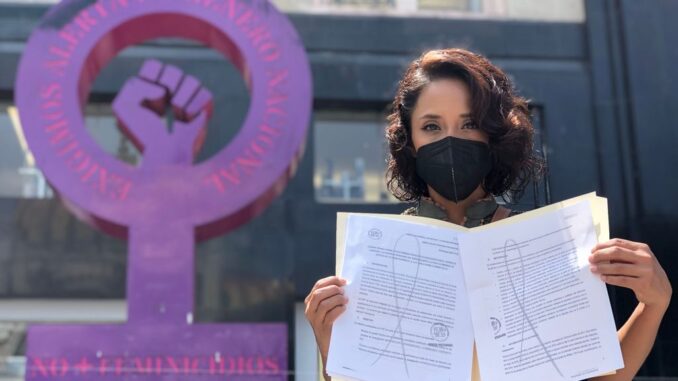

Activist Yesenia Zamudio learned this first-hand.

Zamudio is the mother of María de Jesús Jaimes Zamudio. “Marichuy,” a 19-year-old student from the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), who died in January 2016 of multiple fractures, days after falling from the fifth floor of a building in Mexico City.

The authorities’ first pointed to an accident or a suicide. But Marichuy’s neighbors testified that third parties were involved in the incident. The day she fell, Marichuy had met a teacher and a group of students at karaoke. Later, they all went to Marichuy’s apartment, where a fight led to the tragedy. Now, the teacher and students are all under investigation.

It took two years and eight months for the authorities to reclassify the homicide as femicide. After conducting an investigation, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) issued a recommendation to the General Prosecutor’s office, claiming there had been a human-rights violation against Marichuy.

“The investigation determined that she suffered harassment, as well as student and gender violence within the IPN. The teacher noticed my daughter and harassed her until the last moment. He tried to manipulate her through her grades to get some sexual benefit. My daughter had a scholarship. She always had good grades. As a means of pressure, the teacher failed her,” Zamudio told Zenger.

Almost five years after Marichuy died, the IPN offered a public apology to Zamudio in November 2020. One of the many recommendations the CNDH made to the federal and Mexico City governments triggered the apology.

After holding a meeting with local authorities on Sept. 21, Zamudio told Zenger they had issued arrest warrants against the teacher and one of Marichuy’s former classmates for responsibility in her daughter’s murder. She also said a Red Notice alert had been sent to Interpol, as well as an order filed at the National Institute of Migration to prevent them from leaving the country.

While some women are killed, others manage to escape possible femicide. Karla García belongs to the second group.

Her relationship with her ex-partner could have killed her, she said.

It lasted two years, in which they had a child. The idea of having a family and giving her son a father made her return to him several times. But the violence escalated during their time together.

At first, it was jealousy. Later, he isolated her from friends and family. He constantly checked her cell phone and threatened her. Physical attacks came next. Once, he bit her and tried to suffocate her for not preparing good food, García said.

Once, her partner tried to run her over while taking their son from her home. She jumped on the car’s hood as he pulled out of the parking lot onto the street.

García filed five lawsuits against her former partner, where she described death threats outside her workplace, violence against their son and other events. He presented a psychological examination to the authorities, which the court did not accept.

Her partner was arrested in March 2021, and he is currently serving time in prison. But this is the second time he has been prosecuted. The first time, in November 2019, he was released shortly after, which is why García lives in fear.

“I fear the judge will let him out, allowing him to pay a $35,000 fine. Paying that money, he could leave [prison] without charge, regardless of what happened to me. If the judge does not give him a severe sentence — we are currently seeking to indict him for 24 years — he can pay another amount in court. I fear that he will come out and kill my son and me,” she said.

Monserrat Martínez, a legal advisor for the New Criminal Justice System, said the prosecution should provide its staff with more training on gender perspective. “They provide training during working hours and charge for it, even if it is meant for staff. Besides, staff can’t pay attention to any training when they are serving people,” she said.

In Mexico, the General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence establishes a catalog of emergency protective measures the Public Prosecutor can implement to secure the physical and mental health of the victims and their children.

But Martínez said accessing this resource can be difficult.

“Some victims are taken to a control judge, which means a lot of bureaucracy. Sometimes, the judge does not favor the victims or persuades them not to take this path. It is difficult for the Public Prosecutor to want to implement it. Then come the legal complaints claiming public servants did not implement the protective measures that could have prevented an offense,” she said.

While the authorities work on her case, Zamudio says she has received death threats. Almost six years after the death of her daughter, she demands punishment for those responsible. “We’re devastated, but we are united as a family. We did not do anything wrong. We love Mari, which is why we fight together seeking justice,” she said.

García has also been terrorized by her ex-partner’s circle. “I filed a threat complaint. His partner and family have been threatening me. I do not live in peace, but I am in favor of reporting. If family violence is eradicated, femicides will decrease,” she said.

Translated and edited by Gabriela Olmos; edited by Melanie Slone and Fern Siegel.

The post Violence And Murder Against Women Hit Record Highs In Mexico appeared first on Zenger News.