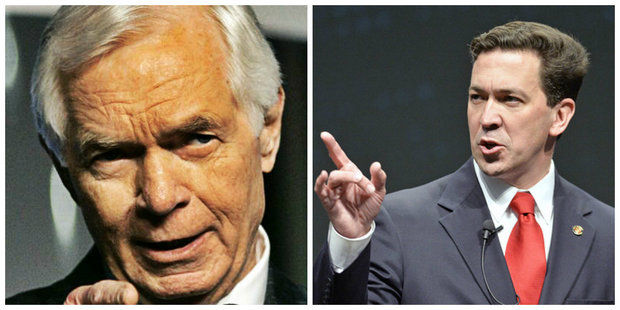

JACKSON, Mississippi (AP) — Six-term Republican Sen. Thad Cochran is trying to survive an intense tea party challenge in Mississippi by reaching out to union members and black voters — two groups that traditionally support Democrats. But he risks a backlash from conservatives ready to support his opponent, state Sen. Chris McDaniel.

Cochran is running TV ads aimed at conservatives by saying he’s the only candidate who has “voted against Obamacare more than 100 times.” And the former Senate Appropriations Committee chairman is traveling the state to remind people that he has brought home billions of federal dollars for projects that transcend party lines. He cites such projects as disaster relief, agriculture and nutrition programs, public education, military installations and highways. Cochran says McDaniel, who pledges to slash spending, could put those at risk.

“My opponent says he’s not going to spend money like I spend money,” Cochran told diesel mechanics last week at a trucking center in Richland. “Well, you’re not going to have any roads and bridges. You’re not going to going to have a lot of things that are essential to our economic betterment and growth opportunities…. Just a word of warning if you’re thinking about voting for my opponent, you need to know that.”

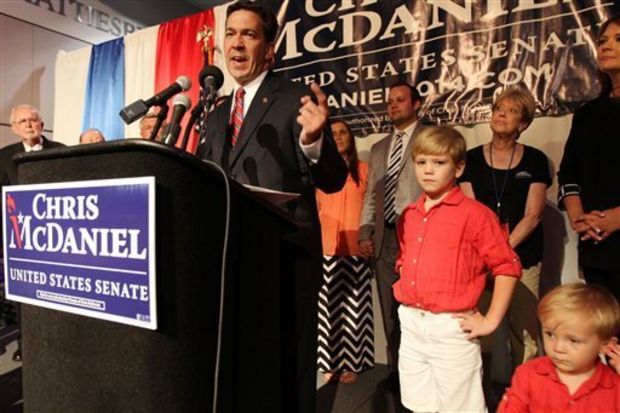

After the shocking ouster of House Majority Leader Eric Cantor in Virginia last week, tea party groups are energized for the next test of their clout: A June 24 runoff between Cochran and McDaniel, neither of whom won the GOP nomination outright in Mississippi’s June 3 primary. McDaniel finished 1,418 votes ahead of Cochran in the three-person contest but fell short of the majority needed to win.

McDaniel’s message: Cochran has piled up a huge federal debt and done little to resist President Barack Obama’s policy initiatives, including the health care overhaul.

“He is pandering to liberal Democrats to save his Senate seat,” McDaniel said Saturday after a campaign stop in the Jackson suburb of Pearl. “It’s a sign of desperation.”

In his last election in 2008, Cochran received 766,111 votes against a Democratic former state lawmaker who ran a low-budget campaign and received 480,915. Cochran campaign staffers say that shows the incumbent has broad appeal, and they believe expanding the electorate for the GOP runoff would give him a boost.

Mississippi voters don’t register by party, so Democrats and independents can vote in a Republican primary. The only ones banned from voting in the June 24 GOP runoff are the 85,866 people who voted in the June 3 Democratic primary.

Mississippi Democratic Chairman Rickey Cole said he has long expected Cochran to seek support across party lines. But Cole said Cochran will have to find any margin of victory from within Republican ranks.

“We like Senator Cochran,” Cole said, “most everyone does. But that doesn’t mean we owe him anything.”

Democratic former U.S. Rep. Travis Childers will be on the November ballot, as will the Reform Party’s Shawn O’Hara, a perennial candidate for governor and other offices over the past two decades. Mississippi last had a Democrat in the U.S. Senate in 1989, and the state has voted Republican in every presidential election since 1980.So, the GOP runoff winner enters the general election campaign with an advantage.

Cochran’s urgency to turn out nontraditional voters for a Republican runoff yielded a surreal scene at a recent pre-dawn shift change at the state’s largest private employer, Ingalls shipyard in Pascagoula — where about 9,000 Mississippians work. Cochran and several supporters — including fellow Republican Sen. Roger Wicker — shook hands with workers and distributed campaign material boasting: “Thad protects our shipyard, our Gulf Coast, our people, our jobs and our way of life.”

During one lull, Wicker and Cochran huddled with two leaders of the local trade unions that endorsed Cochran over McDaniel.

“Can you get your guys out?” Wicker asked Mike Crawley and Warren Fairley, in a rare instance of two Republican senators openly discussing turnout with organized labor leaders. The union leaders said they were confident they could.

Cochran says there’s nothing nefarious about seeking support from a broad cross-section of voters. After Cochran toured a Raytheon defense manufacturing plant in Forest on June 5, he was asked by The Associated Press about reaching out to black voters.

“I think it’s important for everybody to participate,” Cochran said. “Voting rights has been an issue of great importance in Mississippi. People have really contributed a lot of energy and effort to making sure the political process is open to everyone.”

Black residents make up 37 percent of Mississippi’s population — the highest percentage of any state; only Washington, D.C., has a higher percentage at 50 percent. At Mississippi’s Republican dinners or executive committee meetings, it’s often possible to count the number of black participants on one or two hands.

Cochran is hoping all those voters reward him for his support of a wide variety of projects in the state.

One of many buildings named for the senator is the Jackson Medical Mall Thad Cochran Center, an 800,000-square-foot former retail mall that now houses physicians’ offices, an outpatient cancer treatment center and other medical operations. It’s in the heart of a mostly black neighborhood in central Jackson.

Democratic Rep. Bennie Thompson, the longest-serving of Mississippi’s current four House members and the only one who’s black, said Cochran’s work in securing federal money was vital to developing the medical mall in the mid-1990s.

Burtin Willi, 73, came for a checkup because she takes a prescription blood thinner. She said she votes “sometimes, but not very often,” and usually for Democrats. Her situation points to Cochran’s challenge in attracting large numbers of black voters: While Willi said she likes the medical mall because it’s near her home and is a convenient place to go, she said she had never paid much attention to Cochran’s name on the facility.

“I’m not too much into politics,” Willi demurred. “I should be, but I’m not.”