By Monica Land

Lawrence Guyot didn’t have to read about the civil rights movement.

He lived it.

In fact, his memories of the trials and tribulations of the civil rights struggle were so vivid, he constantly shared them with others – including children – so they could understand what the fight was really about.

There was no question Guyot was a warrior for justice and a fighter. He lived to fight for right and his family said he died the same way – fighting – and on his terms.

A Mississippi native, Guyot suffered from heart problems and diabetes for years, and died at his home in Mount Rainier, Md on Thursday, Nov. 22. Guyot was 73-years-old.

According to his daughter, Julie Guyot-Diangone, at least two memorials will be held in his home state of Mississippi to honor her father’s legacy.

On Saturday, Dec. 8, Guyot will be buried at his childhood church, Our Mother of Mercy, in Pass Christian, Miss.

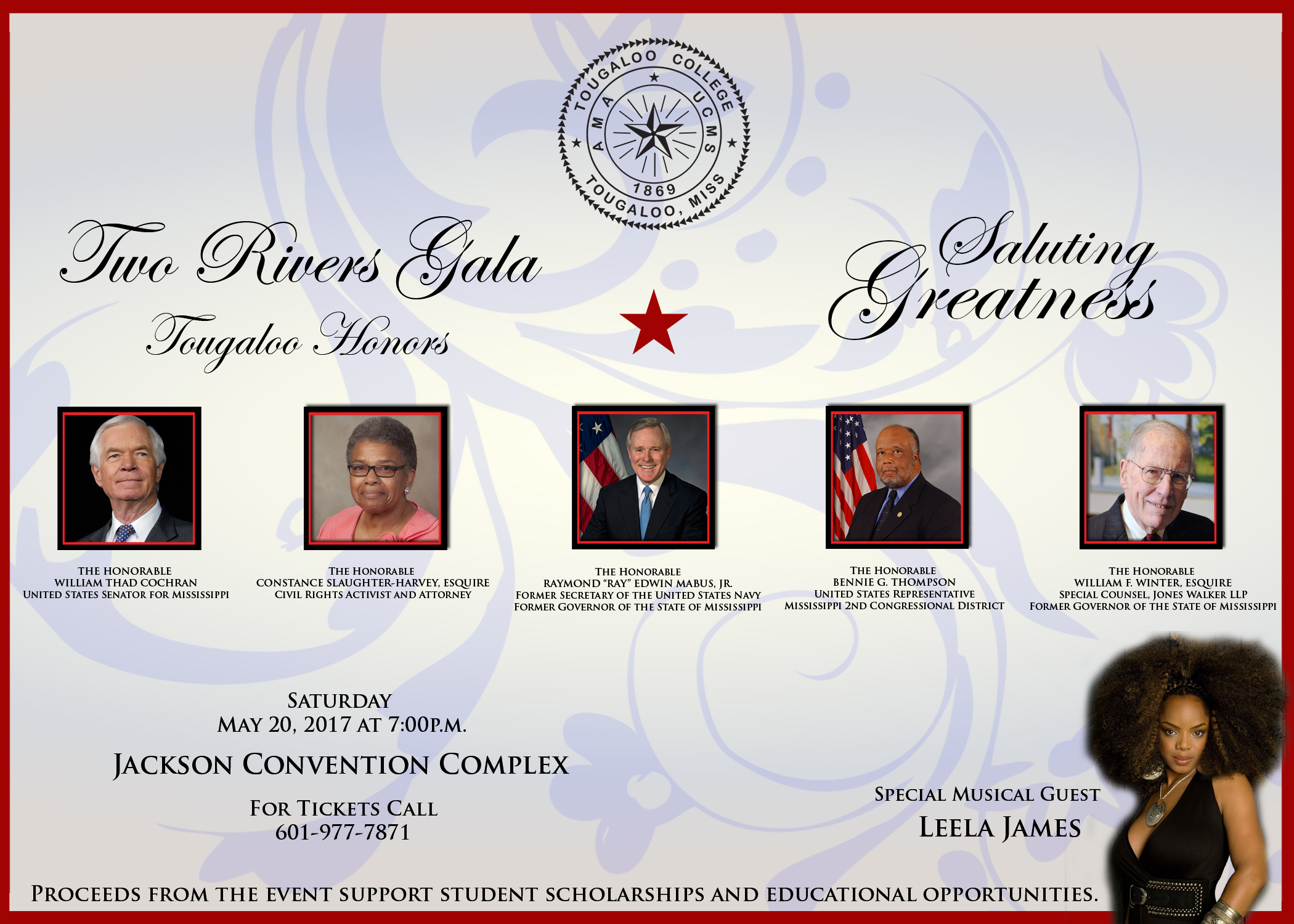

On Monday, Dec. 10, the Mississippi Veteran’s of the Civil Rights Movement and Guyot’s alma mater, Tougaloo College, will host a memorial at the Woodworth Chapel on Tougaloo’s campus. The program will be one of song and remembrance and is scheduled to begin at 6 p.m.

On Saturday, Dec. 15, in Washington, a service will be held at the Goodwill Baptist Church with a continuation at the African American Civil War Memorial on Vermont Avenue. That will be followed by news and film clips of Guyot’s life.

A frequent guest of Bill O’Reilly’s “The Factor,” on the Fox News Channel, Guyot worked and traveled extensively with Fannie Lou Hamer from the first time she registered to vote in 1962 until her death in 1977.

Guyot once said of Hamer: “I was with Ms. Hamer in most of the things that she did. I wasn’t with her in Atlantic City and in a way, I’m glad…because she was the right person at the right time. Her speech has not only been played, but it’s been played and analyzed. Her speech was so effective and powerful that President Lyndon Johnson attempted to stop it. And this is my point. Fannie Lou Hamer was such a key party, such a force in the movement and she operated so effectively politically, that it took the personal involvement of [the president of the United States] to stop us.”

Guyot was with Hamer in June 1963 when they were savagely beaten in a Winona jail in Montgomery County, Miss., after returning from a voter registration drive.

“Ms. Hamer was resolved,” Guyot once said. “She understood that [this struggle] could be dangerous. I was in jail with Ms. Hamer in Winona where she was beaten. I was beaten. Euvester Simpson was beaten. Charles West was beaten and other people. So I saw firsthand that she could and would withstand terror. She stood committed to what she believed in and she didn’t allow that [beating] to stop her.”

Ironically, Hamer, Guyot and the others were released from the jail on June 12, 1963 the day Medgar Evers was assassinated in Jackson, Miss.

Guyot said it was his belief that Evers’ assassination saved their lives.

As an original member of SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), Guyot was interviewed for countless publications, books and documentaries including, Eyes On The Prize, Making Sense of the Sixties, The War on Poverty and Tales of the FBI. He also co-authored, Putting the Movement Back Into Civil Rights Teaching, a resource guide for K-12 classrooms.

Guyot worked with numerous authors and educators including Professor Davis Houck of Florida State University and Maegan Parker Brooks, both of whom edited the recently released, The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer.

“Of his many legacies, one of the most profound and enduring is that of teacher,” Houck said. “He’s had an enormous impact in shaping our memory and history of the civil rights movement by dint of his unflagging commitment to telling the movement’s stories. If you wanted the ‘nitty gritty’ back story, you always went to Guyot — and he always had answers.”

His ability to recall even the seemingly trivial was remarkable. And he in turn gave so much back to my students. We really had a great working relationship. In fact, I’d get stuck in class teaching and I’d ask somebody to get out their phone and we’d call Guyot out of the blue and put him on speaker phone. Totally impromptu. But he never said no, and he always gave the students something memorable. He was infamous for saying that successful organizing ‘was better than sex and more addictive than crack’.”

“He was definitely a towering figure in the movement and he recognized his own force,” author Maegan Parker Brooks said. “He was gracious when it came to sharing memories and information about the struggle, but he was also quite insistent that scholars get the movement right in their depictions. He wouldn’t shy away from calling somebody out on their interpretations, but if you did good work he would defend you until he was breathless!”

I was so honored that he took the time to talk with me about Fannie Lou Hamer, while lying in an intensive care unit in the hospital. Between rough coughs and occasional gasps for air, the memories he shared with me were incisive and crystal clear. He was truly a brilliant man and a warrior for civil rights.”

Entering Tougaloo College at the age of 17 and graduating in 1963, Guyot served as director of the 1964 Freedom Summer Project, which brought thousands of young people to the Mississippi to register blacks to vote despite a history of violence and intimidation by authorities.

He also chaired the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which sought to have blacks included among the state’s delegates to the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

Guyot received a law degree in 1971 from Rutgers University, and then moved to Washington, where he worked to elect fellow Mississippian and civil rights activist Marion Barry as mayor in 1978.

Guyot was severely beaten several times, including at the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary known as Parchman Farm. He continued to speak on voting rights until his death, including encouraging people to cast their ballots for President Barack Obama.

“The doctors basically pronounced him dead on April 13th, when he had his first series of heart attacks and the kidney that had been with him for 25 years began to fail,“ said Guyot’s daughter, Julie Guyot-Diangone. “But [my dad] had stuff to do. He wasn’t finished yet, and spent the next eight months confusing his doctors with his sheer willfulness, his determination to see things through…The doctors shook their heads. They took his numbers. He just wasn’t supposed to still be here. But, the months passed and he continued to organize, ignoring the doctors and his own body. He was going to be the one to make the decision. And he left when he was ready to do so. Not a moment sooner. Even Death had a really difficult time dealing with Guyot.”

Be the first to comment