By Ayesha K. Mustafaa,

Special to The Mississippi Link,

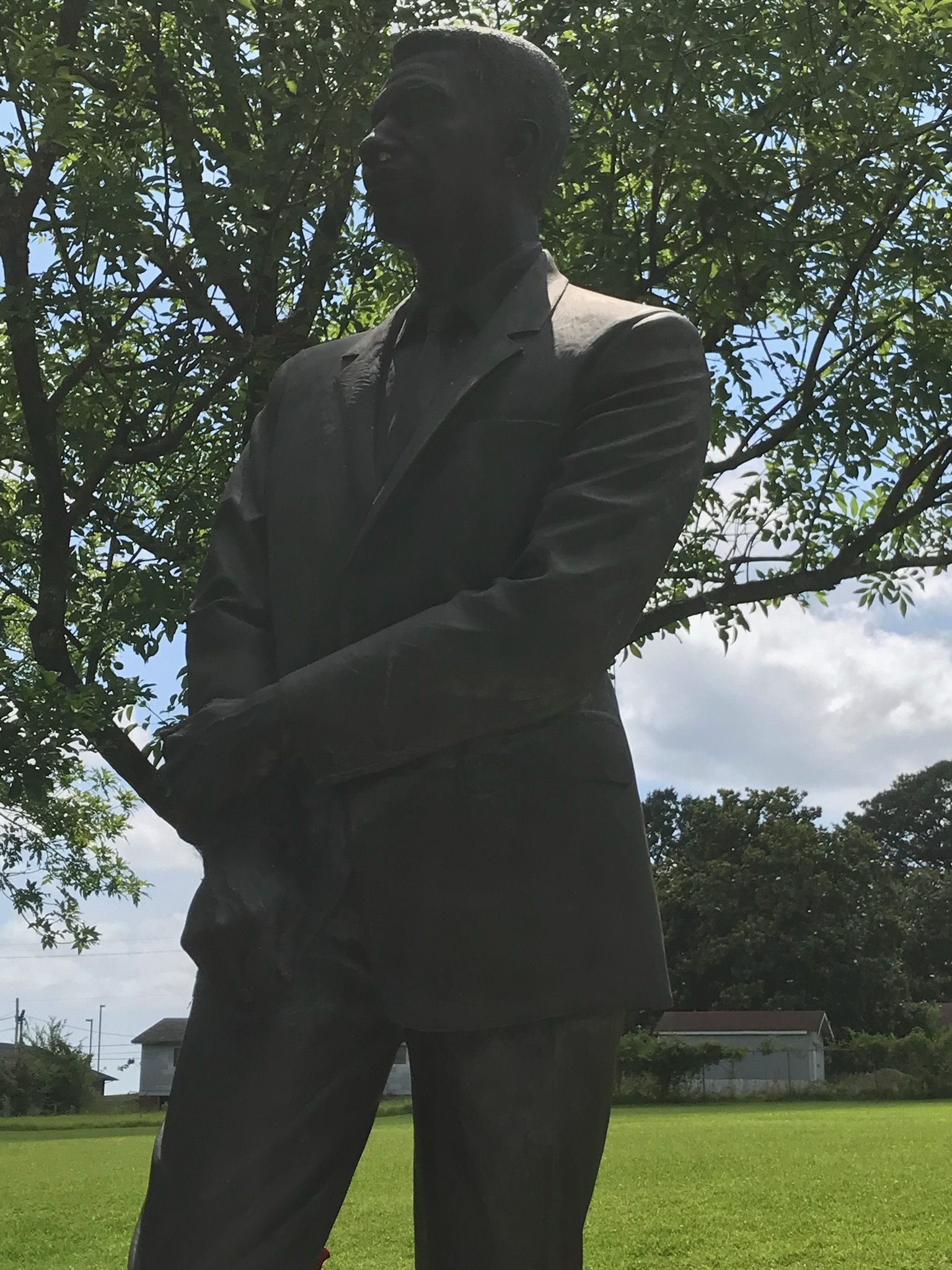

MEDGAR WILEY EVERS, a Native Son, martyred June 12, 1963, gave rise to the phrase: “After Medgar, no more fear!”

The river ran deep in Medgar’s DNA, and he absorbed into his own being his people’s living and suffering. He was appalled by the poverty, the destitution surrounding the African-American population in rural Mississippi.

Born in Decatur, Mississippi, in 1925 to James and Jessie Evers, when he was 12 years old, a family friend was lynched and his bloody clothes left hanging on a fence as a sign of intimidation. (Medgar Evers College/CUNY archives 1970)

He joined the army at age 17 and was sent to the European battlefields of World War II. In Europe, he experienced the same racism with segregated field battalions, just as he’d left in Mississippi.

After three years of “distinguished military service,” he was honorably discharged and went back to complete his high school education. Afterwards he enrolled at Alcorn College (University), majoring in business administration.

He met his life partner Myrlie Beasley at Alcorn; they married Dec. 24, 1951. Soon they moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi – a town with the distinction of tracing its origin to freed African Americans coming out of Davis Bend, Mississippi.

The area Davis Bend was started by planter Joseph E. Davis in 1820 – the elder brother of confederate president Jefferson Davis.

The all-black town, Mound Bayou in the Yazoo Delta of Northwest Mississippi, was established in 1887. There were 12 pioneers who survived falling agriculture prices, natural disasters along with hostile race relations. Yet it was a township “promised to African Americans” where the residents showed a love for self-help, race pride, looking for economic opportunities and social justice.

Think of this environment feeding into the soul of Medgar. It was a “self-segregated community designed for blacks to have minimum contact with whites until integration was a viable option to black freedom.” (https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/mound-bayou-1887/)

Experiencing this life fed Edgar’s discontent which drove him to join the NAACP. While Medgar accomplished much, his true measure is only seen by tallying up the years of “overcoming” and preparation to see his full greatness.

In 2013, the Mississippi State Conference of the NAACP presented “The Life and Legacy of Medgar Evers.” This was the 50-year commemoration of the assassination of the “most noted Civil Rights Leader.”

The fate that sealed him in our memories occurred June 12, 1963, shortly after midnight when he pulled into his driveway in Jackson, stepped out of his Oldsmobile carrying a package of shirts that read “Jim Crow Must Go.”

A sniper’s bullet hit Medgar in the back, the only way a coward would shoot a great man. His wife Myrlie rushed out of their house to find her husband bleeding in the driveway. He was taken to University Hospital’s emergency room where he died within the hour. He was 37 years old.

Medgar had lived the experiences of several lifetimes and accomplished great feats in courage. He knew and lived with danger; he knew what he was facing. He knew people like the sniper who fired that single shot from a high-powered rifle that kept him “forever young.”

Perhaps the great injury was that it took 30 more years – almost the stretch equal to Medgar’s lifetime – to bring the Ku Klux Klan member to justice. Remember, there is no statue of limitation on murder.

As the field secretary for the NAACP in the most racist deadly states in the Union – Ground Zero Mississippi – Medgar led boycotts on white-owned businesses that refused service to Black customers. Messing with people’s money is always dangerous.

According to the Medgar Evers College (CUNY) archive, Medgar’s “organizational skills allowed him to bring together isolated groups of disillusioned individuals and meld them into a unified force.”

He held voter registration drives for the state’s black residents – knowing that others had been murdered for pushing for equal rights of African Americans. In the Medgar Evers College archives (City University of New York 1970), it is written:

He knew you could be killed in Mississippi simply for “being black” (eg Emmett Till), yet he took on the task and filled the role to represent his people. Myrlie said that Medgar was “constantly aware that he could be killed at any time.” Earlier in the year 1963, the Evers home was firebombed. Yet, he continued on the task.

He was in the struggle to overturn segregation of public spaces – no more WHITES ONLY anything. He was a magnet for hostile attention from White supremacists, according to Myrlie moving him up to No. 1 on the “Mississippi to-kill list.”

But Medgar openly talked about why he lived in Mississippi, writing a magazine article to that effect in 1958. He said, “It may sound funny, but I love the South. I don’t choose to live anywhere else. There is room here for my children to play and grow and become good citizens – if the white man will let them.” (NPR June 12, 2023)

The NPR tribute explained that Medgar applied to law school at the all-white University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) and was denied.

The year before his death, Medgar was instrumental in getting accepted into Ole Miss, James Meredith, who applied in October 1962 and had to be “guarded 24 hours a day by U.S. deputy marshals and army troops. Still a riot of angry white men broke out with two people being killed.”

Medgar was remembered in the words of Bob Dylan in tribute at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963, “Only a Pawn in Their Game.” Dylan later performed the song at the 1963 March on Washington led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Dylan’s point was “the sniper” was the “pawn;” there were many other guilty hands. His song pointed to and indicted the guilty “system.” The sniper was white supremacist Byron de la Beckwith, whose fingerprints were found on a gun at the murder scene.

De la Beckwith was tried by all-white juries twice in the mid-1960s, and both times jurors failed to convict him. “On Feb. 5, 1994, a racially mixed jury found him guilty of the murder of Medgar and sentenced him to life imprisonment where he died of heart failure in 2001.

A decade+1 years later and still our beloved Mississippi native son is unmatched in his organizing skills (there were no computers, no cell phones, no social media). He organized, motivated and activated “the old fashion way” – man-to-man, woman-to-woman, church-to-church and plenty of shoe leather and hours on the clock.

At that 50-year celebration, June 12, 2013, the late Civil Rights activist Vernon Jordan said: “All this change you see in Mississippi is a tribute to Medgar’s sacrifice and service and courage and smarts.”

The late former Governor of Mississippi William Winter said, “What he (Medgar) did freed us white folks as well as black folks.”

Sixty-one years later and we still remember and appreciated how Medgar planned, organized and enacted events aimed at restoring freedom and dignity to all African Americans impacted by Jim Crow laws, racist humiliations and as Medgar’s is a testament – murderous rage.

At the 2013 tribute, Medgar’s beloved widow Myrlie Evers-Williams closed the tribute simply saying, “We love you, Medgar.” We all – as Gov. Winter said, blacks and whites owe Medgar with so much more than we can repay.

So, we too want to say, “We love you Medgar.”

Be the first to comment