Special To The Mississippi Link

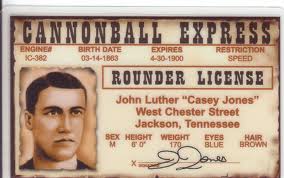

WATER VALLEY – The Mississippi Blues Trail recently honored John Luther “Casey” Jones with a marker in an unveiling ceremony at 105 Railroad Avenue in Water Valley.

On April 30, 1900, Jones, a railroad engineer, died when his Illinois Central train, the “Cannonball,” collided with a stalled freight train in Vaughan, Miss.

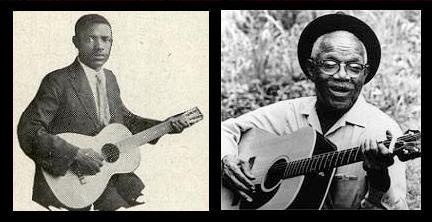

Jones, who once lived and worked in the railroad town of Water Valley, was credited with saving the lives of his passengers and crew, and he was immortalized in song by many artists, including Mississippi-born bluesmen Furry Lewis and Carroll County native, Mississippi John Hurt.

Jones was fatally injured when “The Cannonball Express,” crashed into a northbound train, which had failed to pull completely onto the siding. The crash occurred just north of Vaughan, Mississippi. Jones was found in the wreckage and carried to the Vaughan Railroad Depot where he died a short time later.

The railway engineer occupied a celebrated role in the American cultural imagination during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the peak era of the steam locomotive.

None achieved more acclaim than “Casey” Jones, although his exploits – true and otherwise – only became popularly celebrated years after his death.

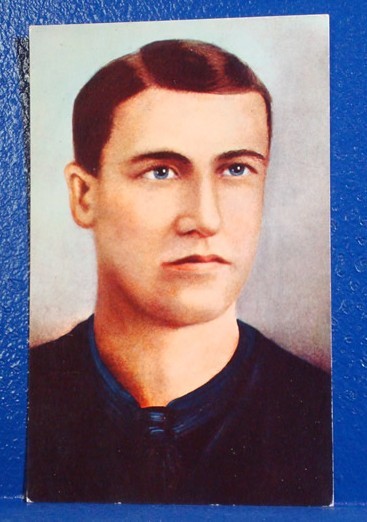

A native of Cayce, Kentucky – the source of his nickname – Jones (1863-1900) began working for the Illinois Central as a fireman in 1888. Two years later, he joined the Water Valley lodge of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, and at some point moved to the city, which housed a major roundhouse and shop for servicing locomotives.

In 1891, Jones was promoted to engineer, and in 1900 began working on the Memphis to Canton, Miss., stretch of the Cannonball line, which carried passengers and mail between Chicago and New Orleans.

Around 1 a.m. on April 30, Jones and Sim Webb, a black fireman, boarded engine No. 382 in Memphis, where the Cannonball had arrived an hour and half late.

Jones was almost back on schedule as he approached Vaughan shortly before 4 a.m., but as he rounded a curve just before the station he encountered a stalled train. He ordered Webb to jump, and died with his hand still on the brake as he crashed into the train’s caboose, but his passengers suffered no major injuries.

These basic facts were missing from many of the subsequent songs and stories about Jones, which often altered the story by imagining the reaction of his family, introducing new characters (including other engineers reputed to be “the real” Casey Jones), changing the locations and exaggerating Jones’ exploits.

After the wreck, Wallace Saunders, an black worker at the Canton roundhouse who knew Jones, composed a ballad (with some verses reportedly added by fellow employee Ike Wentworth) that spread widely among railway laborers.

These included Cornelius Steen (or Stein), whose version was recorded by folklorist John Lomax in Canton 1933. Saunders’ ballad was first published in a railroad magazine in 1908, and the following year the first sheet music version appeared, credited to T. Lawrence Seibert and Eddie Newton.

In 1910 a recording by vaudeville singer Billy Murray reputedly sold over a million copies, and the first country music version was recorded by Fiddlin’ John Carson in 1923.

The first issued blues recording was Furry Lewis’ two-part “Kassie Jones” from 1928. Mississippi John Hurt recorded “Casey Jones” earlier in 1928 but it was never released; in the 1960s he recorded multiple versions. Bluesmen Jesse James and Bob Howard both recorded “Southern Casey Jones” in the 1930s.

The wide range of artists who subsequently recorded Casey Jones songs included Johnny Cash, Sidney Bechet, Spike Jones, and the Grateful Dead. The Jones saga was also popularized via newspaper and magazine articles, stage and cinema productions, a TV series, toys, trading cards, a comic book, and museums including the Water Valley Casey Jones Railroad Museum, which opened in 1997.

Casey Jones lived in Jackson, Tennessee and is buried in Jackson’s Mount Calvary Cemetery.

Be the first to comment