NEW DELHI — Around the same week that Italy officially abolished film censorship, India scrapped its movie certification tribunal, leaving several filmmakers debating on whether this is a step forward or backward.

The Tribunals Reforms (Rationalization and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021, issued by India’s Ministry of Law and Justice on April 4, did away with the Appellate authorities across nine laws.

The Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT), established in 1983 under the Cinematograph Act 1952, served as a platform for filmmakers aggrieved by decisions of the country’s Central Board of Certification (CBFC).

It would either reaffirm or reverse the CBFC’s decision. But now, the only recourse for filmmakers is to approach the high courts.

Filmmaker Ritesh Batra, director of internationally acclaimed “The Lunchbox” (2013), wrote: “It’s not good for art or business to direct filmmakers to an overburdened judiciary.”

“Such a sad day for cinema,” noted filmmaker Vishal Bhardwaj tweeted.

However, filmmaker Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri, who is on the CBFC board, said in a tweet that he has observed that hardly any producer goes to the FCAT.

“Instead, they prefer to go to the high court,” he said. “The FCAT refers disputes back to the review committee. Why should taxpayers pay for a redundant tribunal?”

The move comes weeks after the Indian government exercised control over digital news media and online video streaming platforms by introducing a three-tier mechanism and terming it a “soft-touch regulatory architecture”.

Typically, in India, films are submitted first to the censor board’s examining committee, which suggests beeps and cuts if needed, before giving it a certificate for a theatrical release. If a movie does not get the green light, filmmakers can appeal to a revising committee for certification. And, until now, if this also did not work, filmmakers went knocking at the FCAT’s doors.

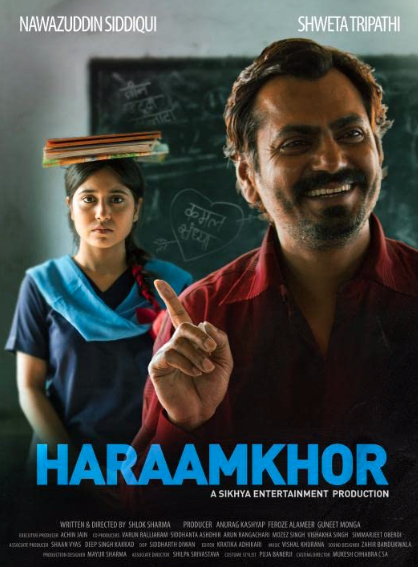

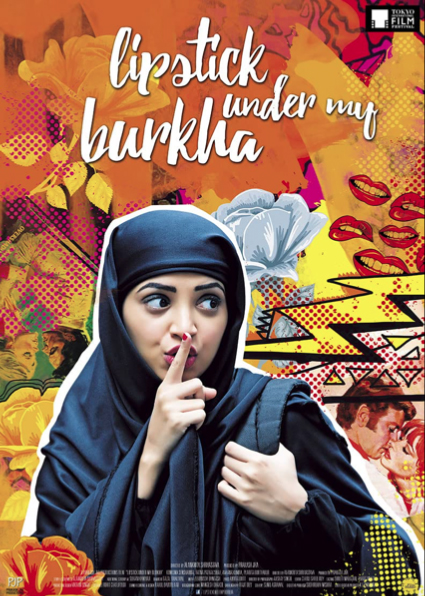

Movies such as “Haraamkhor” (2015), “Lipstick Under My Burkha” (2016), and “Babumoshai Bandookbaaz” (2017) took that route and got cleared for release with minimal cuts.

The FCAT had famously overruled the CBFC’s decisions regarding Shekhar Kapur’s 1996 film “Bandit Queen”, allowing the film to release with an ‘A’ certificate.

“The CBFC (then led by Pahlaj Nihalani) threatened us with 48 cuts for our film,” Kushan Nandy, who directed “Babumoshai Bandookbaaz”, told Zenger News. “I had no option but go to the FCAT, which threw around 43 of them [suggested cuts] out of the window.”

Nihalani has previously said the CBFC has the onus to preserve the country’s culture and tradition.

For Nandy, the shutting down of the FCAT is “shocking”.

“Here was a far more liberal and independent body understanding the creative voice of a filmmaker, without any personal agenda,” he said.

“Closing down of the same means filmmakers are expected to go to court, spend a fortune, and let the film lie in the can for years. Which filmmaker will do that?” he questioned, summing up the concerns of most filmmakers who are upset by the move.

What made the FCAT a saner voice?

Actor Poonam Dhillon, who became a part of the FCAT committee in 2016, told Zenger News that the interpretation and adaptation of the members, who came with a huge body of work across disciplines of law, journalism, or films, was in tune with the times and more rational and balanced as compared to the CBFC.

“Over the last few years, the number of films needing to go to an Appellate body has seen a steady decline,” CBFC chief Prasoon Joshi said in a statement. “Over the past two to three years, only around 0.2 percent films were taken to the FCAT, and I am sure this gap can be further closed.”

Dhillon contested by saying “it is a good thing” if only many films need to appeal to another body after the CBFC. “But even if it is 1 percent or lesser, if filmmakers require relief, they should get it,” she said.

She believes abolishing the FCAT, an “expeditious” layer between the CBFC and the courts, will be “detrimental” to the industry.

Worried about the burden the decision will cause to hapless filmmakers amid busy courts, Dhillon said if a decision about FCAT was taken with 2020 as a benchmark, it is a “false reading” as hardly any films were releasing anyway.

Film censorship has been a widely debated subject in India.

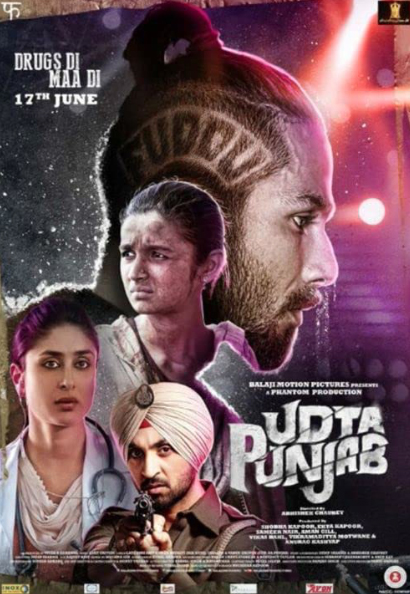

At one point, the makers of the Bollywood film “Udta Punjab” — showing the drug abuse problem among youth in India’s northern state of Punjab — compared the CBFC’s functioning to dictatorial North Korea after they were asked to remove all references to the state.

This is one of the many instances where the CBFC asked filmmakers to either remove or replace a scene, word, song, or object in a film to get the certification.

Filmmakers have, for long, been calling for an overhaul of the film censorship system that dates back to the 1950s and asking for the implementation of an up-to-date age-based certification mechanism.

In 2016, there was hope for change when the government formed a CBFC revamp committee, headed by acclaimed filmmaker Shyam Benegal, to suggest a fresh mechanism for film censorship, ensuring that artistic creativity and freedom are not curtailed.

The committee submitted an exhaustive report suggesting categorization and certification of films according to age — as is done in most countries, and snipping the scissors out of the CBFC’s hands. But its implementation is in limbo.

Filmmaker Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, a part of the committee, said the revoking of the FCAT is “definitely a step back, not a step forward”.

“This is too ad-hoc a decision, and it is not going to solve the problem of misuse of expression that they think it would,” the “Rang De Basanti” director told Zenger News. “Discipline is one thing and fear another. Just by instilling fear, the content is only going to get mediocre.”

In a democracy, Mehra said, having a voice that expresses itself is the starting point. “That’s not where you work towards,” he said, adding that if at all a step was to be taken, “we should have addressed the idea of censorship, to begin with”.

(Edited by Amrita Das and Gaurab Dasgupta)

The post India Abolishes Film Certification Tribunal, Filmmakers Split appeared first on Zenger News.