By Shanderia K. Posey

Editor

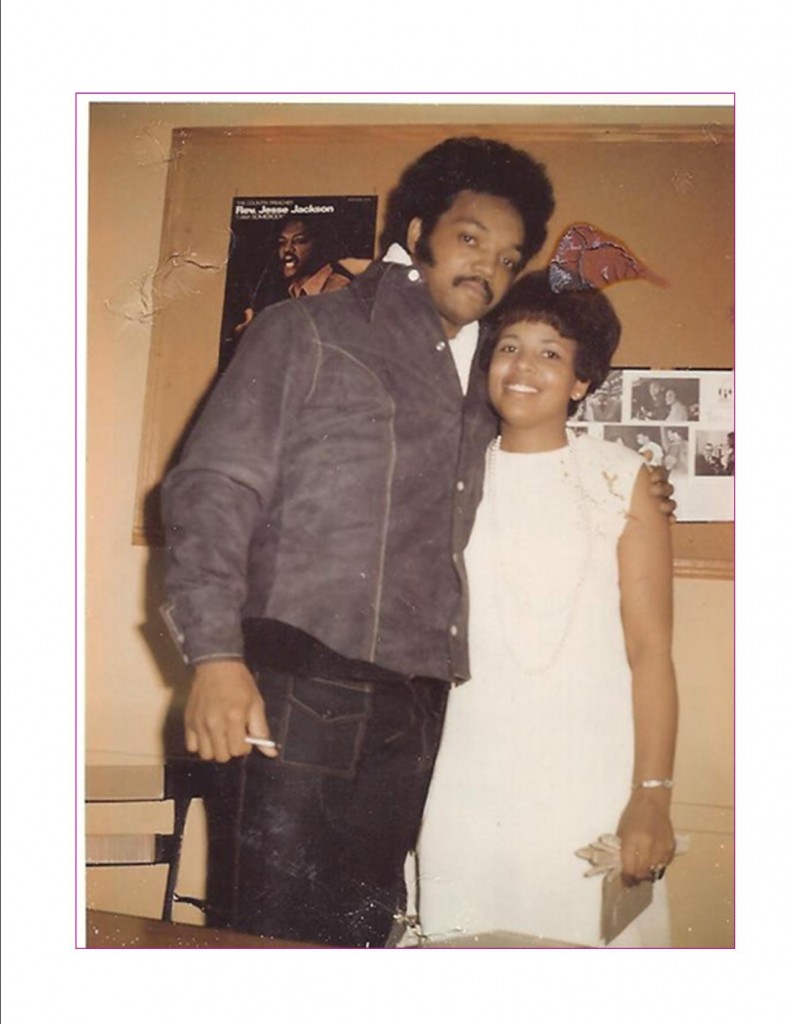

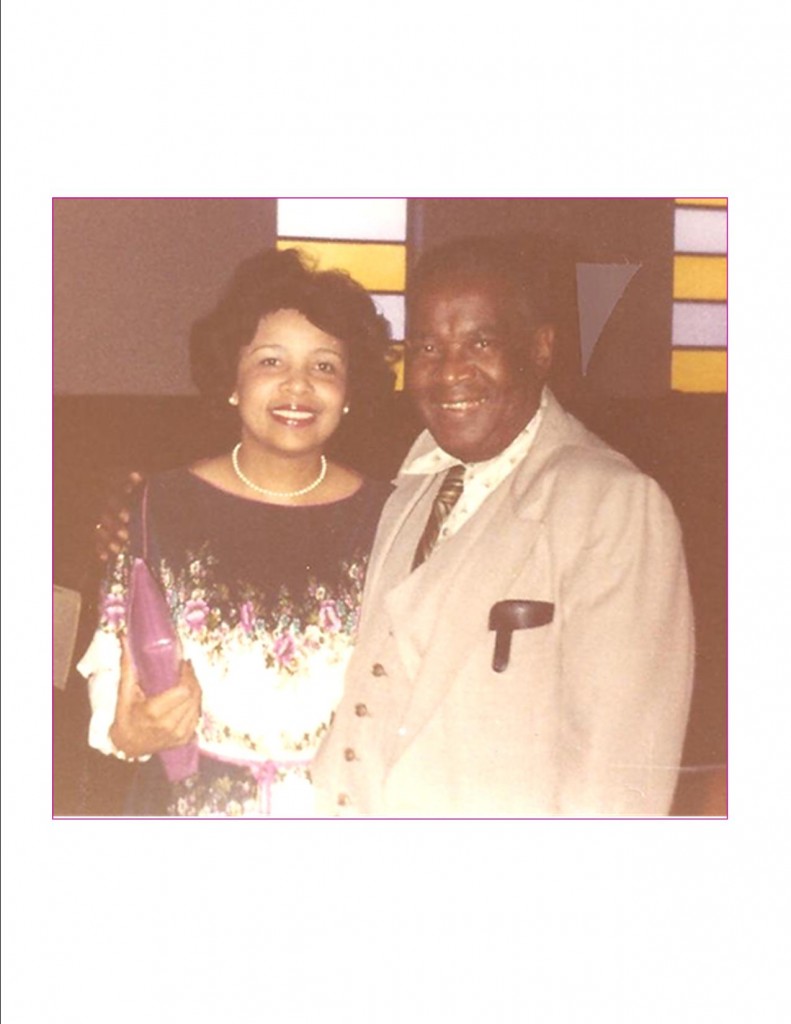

Flonzie Brown-Wright, 73, a Mississippi civil rights icon who fearlessly worked to get blacks registered to vote in the 1960s, has been recognized numerous times for her work.

She was the first African-American woman to be elected to public office in Mississippi since Reconstruction.

But this Friday’s event – the dedication of a Canton City Hall courtroom in her honor – may surpass previous recognitions.

The courtroom in City Hall is also the same place where her father – Frank Brown Sr. – was denied his plumber’s and electrician’s license about 60 years ago. Her father took the test to receive the license three times in the room, and though he passed every time, the superintendent failed him every time. Brown-Wright says that on his death bed, the superintendent called for her father and apologized for what he had done, telling her dad, “Will you forgive me ‘cause every time you took that test, you passed, but we were not ready to allow a black man, a colored man to unstop a toilet with a license.”

Eventually, her dad did receive his license.

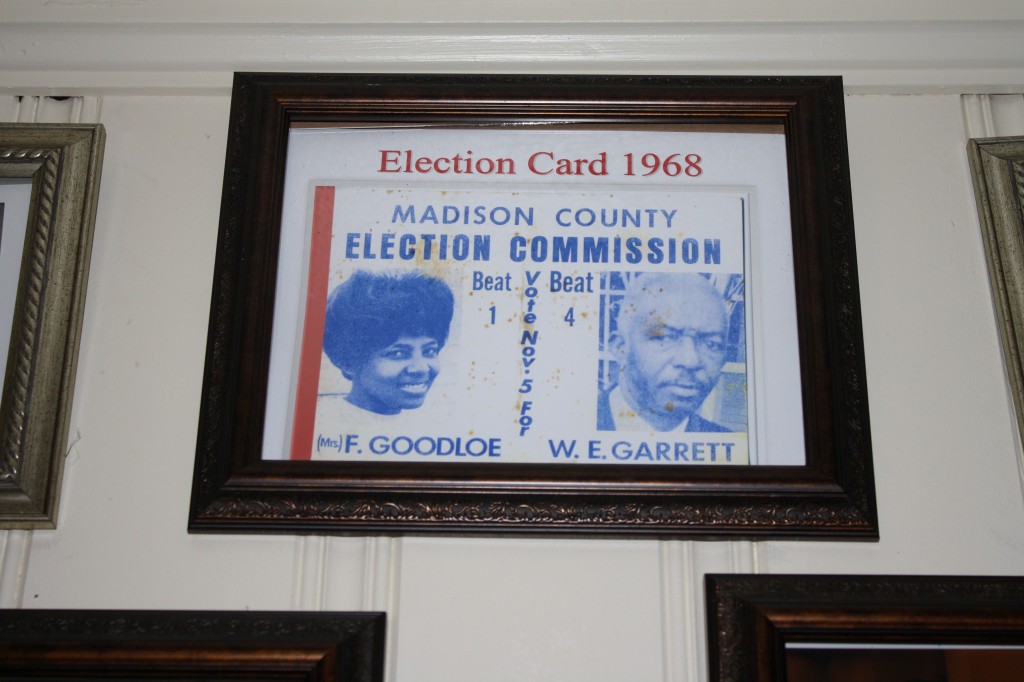

Around 1965, Brown-Wright was Canton’s NAACP branch manager. Typically, she brought groups to the Madison County Courthouse to register to vote, but one day she went alone to register herself.

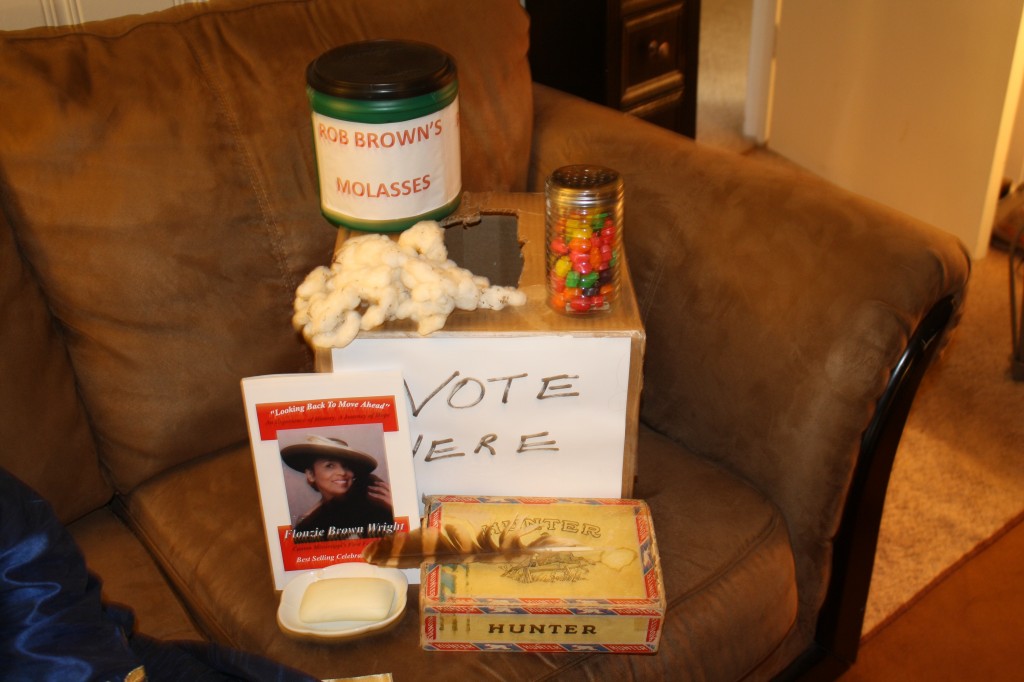

“My experience was like many other blacks. You went to the courthouse. You got a 21-item, two-page questionnaire … when you got to item 17, you went to the registrar’s office and reached into a cigar box and pulled out a section of the Mississippi Constitution. The section that I pulled out was on Habeus Corpus,” she says.

Very few blacks knew what that section of the Constitution meant, but Brown wrote something. She figured if the registrar – L. Foote Campbell – was having a good day, he would allow her to write her name on the registration book. After finishing the questionnaire, she asked Campbell how she did and he told her she didn’t pass. Then she asked in a calm tone what was her mistake.

“I knew not to get too loud because the sheriff’s office was right across the hall. I could have been pulled out of there, thrown in jail, beaten up, killed,” she says. Then Campbell told her, “Nigger, I told you, you didn’t pass. You get the hell out of my office.”

That’s how all blacks were treated Brown-Wright said, not just her.

Around this time, a lot of people in town were asking her to run for office, but she had no interest in politics – until the day Campbell put her out of his office.

“The day he cursed me and put me out of his office, I determined walking down the corridor of that courtroom . . . I resolved within myself that day that I was going to run for office, and I was going to get his job.”

Brown-Wright was elected election commissioner of Madison County, Beat 1, Nov. 5, 1968.

In October 2015, the Canton Board of Aldermen named the courtroom in City Hall the Flonzie Brown Goodloe Courtroom. The dedication will take place at 11:30 a.m. Friday at City Hall.

From the time he was elected in 2013, Canton Mayor Arnel Bolden knew he wanted to do something to honor Brown-Wright.

“I’ve known about her tremendous strides (in civil rights) for years. I wanted to give her her flowers now. It’s a fitting tribute,” Bolden said. “As elected officials, we stand on the shoulders of those like Brown-Wright.”

As it turns out, Brown-Wright’s work in the Civil Rights Movement almost didn’t happen.

She grew up in Farmhaven, and her family moved to Canton when she was about 5.

“There was lots of love in our family. Lots of affirmation,” she said. Her parents – Frank Brown Sr. and mother, Little Pickett Dawson Brown – constantly told her and her two brothers, “You can be whatever you want to be. If anybody else can do it so can you.”

Her father worked hard being the first among his siblings to build a home for his family. Her mother took care of the home. They didn’t believe in handouts.

Her mother always said, “When you earn a dollar no one can take it from you, but if they give it to you they can ask for it back.”

Discrimination just wasn’t something that was discussed in their home.

In 1958, Brown-Wright left Mississippi to live in California. She returned in 1962 to care for a cousin who lived on the Coast and worked in Biloxi as a waitress.

Daily she served three black attorneys.

“I would hear them talking about integrating the beaches, going to the meetings, talking about who went to jail, who got beat up and who was missing,” she said.

One day Attorney Jack Young mentioned how he hadn’t seen her at their meetings and told her she should attend to help with the Freedom Movement.

She went one night to a meeting at a church. “That church was rocking with freedom songs and speakers,” she said.

During the time she was attending regular meetings, Medgar Evers was murdered on June 12, 1963.

“And that really set me on fire,” Brown-Wright said.

She went back to Canton, a place that was pivotal in the Civil Rights Movement because of its population of potential African-American registered voters. There were at least 10,000 potential registered voters but only about 100 blacks – mainly pastors and school teachers – who were registered.

“When I came back to Canton, I was ready. I never saw myself as a leader. Never saw myself as person who wanted fame, but just as a person who was on a mission,” she said.

Charles Evers appointed her to be the branch manager of the NAACP office in Canton, which at the time was defunct. The NAACP, SNCC, CORE, COFO, The Freedom Movement, Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party all worked collaboratively to gain the right to vote.

Brown-Wright has worked with several icons in the Civil Rights Movement including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, Annie Devine, W.E. Garrett and Aaron Henry, just to name a few. She met Vernon Dahmer on a couple of occasions. King called Brown-Wright directly after he took over James Meredith’s March Against Fear in June 1966, following Meredith being shot.

“I knew who he was (on the phone) because of the voice inflection. It’s hard not to know King’s voice. He asked, ‘Can you provide housing and food for 3,0 00 people?’”

She agreed.

“I didn’t get nervous about it until I hung up the phone,” she said. But after several calls and visits to merchants, friends and businesses, people agreed to open their homes and cook for the marchers that were coming to town.

Nothing deterred Brown-Wright from her work for equality – not even being a divorced mom of three children – two boys and one girl. She once worked three jobs at a time to provide for them. Her daughter, Cynthia Goodloe Palmer, is executive director of the Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement at Tougaloo College.

Palmer says her mother constantly affirmed her and her brothers when they were growing up.

“She told us we could be anything we wanted to be. Be respectful and do the right thing. Surround yourself with positive people,” Palmer says. “I don’t think she really realizes the extent of what she did during that time. She did put her life on the line. The sacrifices she made still make an impact. She just keeps going and going. She was fearless. That’s where I get that from.”

Brown-Wright, who attended Tougaloo College, left Mississippi again and moved to Ohio in 1989. She worked for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission from 1974 to 1989. She returned to Mississippi in 2010.

She describes life now as a “mixed bag.” She still hurts at times over the loss of very close loved ones. Both of her parents died at age 89. Both of her brothers passed at age 69. One son – Edward Goodloe Jr. – passed at age 53. Her son, Lloyd, moved back to Jackson in September 2015 to be closer to his mom.

She stays busy giving lectures on her civil rights experiences. She’s on the lecture Board of the Mississippi Humanities Council, is a founding member of Women of Progress and attends New Hope Baptist Church in Jackson. Overall life is good.

“I love the Lord, He takes care of me here. I’m having a good time living.”

Be the first to comment