JACKSON, Mississippi (AP) — Should Mississippi gear its prison policy to produce free inmate labor for local governments? The answer that some sheriffs, county supervisors, lawmakers and others are giving seems to be yes. The fuss is over Corrections Commissioner Marshall Fisher’s decision to shutter the Joint State County Work Program. It’s a hangover from the Legislature’s 2014 decision to reduce inmates in state prisons. Then, most people seemed happy about dialing back on prison sentences. Republicans wanted to spend less money on the Corrections Department and Democrats wanted fewer harsh sentences. That was a reversal of Mississippi’s decades-long pattern of imprisoning a lot more people, leaving the state with five times as many inmates as in 1980. That rate of increase was greater than the nation as a whole, and it made the Magnolia State a world leader in incarceration. Mississippi had the second-highest rate of jailing people among states in 2013, behind only Louisiana, according to the Sentencing Project. And the United States as a whole trailed only the tiny island nation of the Seychelles in its rate of locking people up. While civil rights advocates have complained about over-incarceration, Mississippi’s prison industrial complex has benefited some. For example, the bribery opportunities for now-convicted Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps were probably more lucrative because of the state’s large and growing number of inmates. And the state needed places to house prisoners. One solution was regional jails, 15 facilities mostly in rural and depressed areas. Counties borrowed to build them with the promise of state inmates, creating some jobs. Other local governments facilitated borrowing for private prisons. When Mississippi had more inmates than it knew what to do with, county work programs were another place to stash them. There too, counties borrowed to build special facilities to host non-violent offenders nearing the end of their sentences. But with the prison population falling, both the county programs and parallel state-run Community Work Centers are about half empty. Fisher has sided with preserving his own employees’ jobs, closing county facilities instead. “The taxpayers are going to be left holding the bag for that,” Mississippi Association of Supervisors Executive Director Derrick Surrette said of indebted counties last week. But more acute is the disappearance of the inmates. More inmates mean sheriffs get to hire more jail guards, and local entities get an estimated $23 million in free labor. Carthage Mayor Jimmy Wallace noted inmates have helped repair churches in Leake County, a sure source of electoral goodwill. Advocates say taxpayers deserve to have inmates riding garbage trucks or painting county buildings. “One of the most positive things is the taxpayer telling us they’re glad to see the prisoners out there doing that work, not lying in some bunk bed in Parchman,” central district Transportation Commissioner Dick Hall said of his department’s contracts with counties and cities to have inmates pick up roadside litter. “The taxpayers are paying for that guy to be out there doing that work, they’re feeding him and clothing him and housing him. They want him out there doing something, not piddling away somewhere.” Although it’s hard to see the lucrative future of roadside litter collection, supporters argue some inmates are learning skills like carpentry or auto repair that will help them in the outside world. . “We’re also teaching these guys skills once they’re released from prison,” Wallace said. Lawmakers and candidates are piling in too, trying to save the program. Rep. Tommy Reynolds, D-Charleston, is proposing widening the number of prisoners allowed to participate. “We need to change the law to make even more people eligible for this program,” he said.

Related Articles

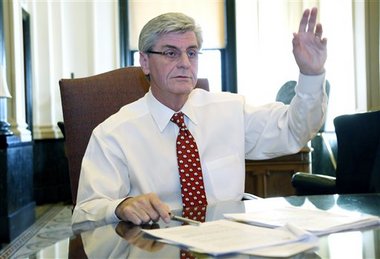

Gov. Phil Bryant declares state of emergency for 12 counties with storm damage

JACKSON, Mississippi (AP) — Gov. Phil Bryant has declared a state of emergency in 12 Mississippi counties that have suffered impacts from flooding and severe storms that moved through the state beginning April 3. The […]

Protests against President Obama re-election: Ole Miss and Donald Trump

By Lonnie Ross

Not all Americans were happy about the re-election of President Barack Obama, the first African American president in the history of the United States and the first African American to be re-elected to the same office.

Some citizens decided to express their disgust with the election results publicly on social media and on the streets.

Donald Trump, the outspoken businessman and reality TV star told his Twitter followers Tuesday night he wants Americans to march on Washington to protest the “great and disgusting injustice” of Barack Obama being re-elected as U.S. president…. […]

Thompson at the ‘Hill’

By Daphne Higgins Religion Editor Just as he did in 2000, Congressman Bennie G. Thompson had the members and guests of College Hill Missionary Baptist Church of Jackson clapping in agreement from the message he […]